Ross G Caldwell

(the following is the text of my presentation before the annual conference of the International Playing Card Society in Issy-les-Moulineux, September 2006. It presented some information published first on Aeclectic.)

THE DEVIL AND THE TWO OF HEARTS

Some new documentary discoveries of magical or "superstitious" use of cards from the earliest centuries deserve to be shared with the IPCS. These are not isolated or unexpected uses, when understood in the context of the early use of printed images. The material can be divided into two broad areas - devotional use and magic, and divination. While this is an arbitrary distinction, since divination is a category of magic, it helps me present the material.

I. Jean Jordain

The title for my talk comes from the following story about Jean Jordain. Jean Jordain was a young man who was tried in 1614 for witchcraft and sacrilege, part of which was making a pact with the Devil on two playing cards, a two and a four of hearts.

The trial of Jean Jordain took place in Blaye, on the Gironde north of Bordeaux in 1614. An account of the events was related by Pierre de l'Ancre in 1622, in his book "L'incredulite et mescréance du sortilège, plainement convaincue" (The disbelief and misbelief in witchcraft, plainly convinced).

Pierre de l'Ancre was born in Bordeaux in 1553. He studied law and philosophy in France, Bohemia and Turin. He became councilor to the Bordeaux parliment at the age of 29 in 1582, and in 1588 he married Michel de Montaigne's grand-niece. He was well acquainted with the leading intellectuals and political figures of his day. Because of his familiarity with the region, in 1609 Henri IV sent him to find and prosecute witches in the district of Labourd, in the extreme south-west of France. Travelling with another judge, de l'Ancre found the region completely infected with witches, and by the end of their inquisition, about 500 people had been burned at the stake for it.

The context of the period is described by Joseph McCabe, in his 1948 book "A History of Satanism". It should be remembered that at this time witchcraft was seen as a vast and unified movement of Devil-worship, an anti-religion.

"[The prominent jurist] Boguet condemned the use of torture, and L'Ancre and his colleague, another eminent judge and royal counsellor, used it only in two or three out of many hundreds of cases. At first they encountered a baffling silence. The priests, who wore swords and picturesque costumes and drank and danced with the villagers and townsfolk, were—it transpired—in the movement and instructed folk to say nothing. Large numbers of the women took to the sea in their husbands' boats or went on pilgrimage to Spain; where the cult was even stronger. At last, by torture or more amiable means, the judges won the confidence of a 17-year-old and fiery beggar girl—she danced the witch-dances for them—and they broke the conspiracy of silence. Here we have a competent lay judge reporting, without using torture, just the same chief phenomena as the Inquisitors. Some of the highest nobles and most of the priests attended the Sabbaths, and the priests said Black Masses. At one place there was a gathering of 12,000 witches. Educated women in their later 20's told how Satanism was the best religion, and they would rather go to the Sabbath, the "real Paradise," than to the Mass. It was a foretaste of their joy in the next life. This referred to the usual orgy of promiscuity. The Sabbaths, to which they took about 2,000 children to be initiated, were held nearly every night and sometimes during the day. As the trials proceeded the large fleets of fishing boats came in from the Atlantic, and the anger of the men at the prosecution seems to have forced the judges to close it prematurely. But, says L'Ancre, "an infinite number (really about 500, including several priests) were burned at Bordeaux and in Brittany"—which suggests that the cult spread along the coast. In fact, there were almost simultaneous persecutions on a large scale all over France. At Macon the jails were full, and there were trials at Orleans and other places."

Additionally,

"Whole communities of nuns were said to have been surrendered to the Devil. From Marseilles in 1611, the year after L'Ancre's inquiry, it was announced that the Ursuline nuns in one of the most respectable convents were dealing with the devil, and a number of them were "possessed.""[End]

Religious hatred was also in the air. By this time, the Edict of Nantes in 1598 had only recently stopped the bloodshed and destruction of the Hugenot wars, which had ravaged relations between Protestants and Catholics since 1562. Tensions were still rife, and both sides considered the other in league with the Devil.

It is this paranoid context that the trial of Jean Jordain took place. (the italicized text was summarized)

Pierre de l'Ancre devotes 20 pages to the story in his book - here are the essential details.

Jordain was born around 1589 in the small village of Moras near Agen. In March of 1614, at the age of 25, he was working as chamberlain to the lord of Castanet, Monsieur de Barastre. Jordain fell in love with the children's nanny, and proposed marriage to her, swearing, according to de l'Ancre, that the "Devil could take him if he didn't fulfill his promise to marry her". De l'Ancre takes this a darkly prophetic. The girl accepted and they consummated their love. But Jordain's affections seem to have changed, when the girl believed she had become pregnant. She entreated him to marry her immediately, but he continually urged her to have patience.

She soon realize that Jordain had no intention of marrying her, and in tears and rage appealed to Monsieur de Barastre to intervene. Sensing that he would be severly punished, Jordain fled to his family, and then, still feeling in danger, he went to Blaye, where he had earlier served the prior of the Church of the Holy Saviour, a Pierre de l'Espine.

His conscience continued to torment him, however, and he took long walks alone to clear his mind. About three weeks after his arrival in Blaye, during one of his pensive walks, he was suddenly afflicted with a massive head-ache, and saw a thick black fog in front of him.

Out of this fog walked "a man who appeared all hunched over, dressed in a robe of black silk, of medium height and sturdy, having a long beard and black hair, which like straps, blowing across his shoulders and face. He seemed blind in the right eye, without a cloak, a sword at his side, with bare feet." It was the Devil, Satan himself.

On this first meeting, which lasted about an hour, the Devil cajoled Jean with promises and finally presented a pact for him to sign, which Jean, being illiterate, could not read. The Devil said he could help him learn to read and write, but it would be enough for him to copy the pact letter by letter. Jean wouldn't do it, and finally, he began to go away, and finally, with a terrible smell - Jean said "Jesus Maria, you stink something awful!" - the Devil departed, promising to come back next Saturday at the same time.

He had several more meetings with the Devil, and it is interesting to see the rewards Jordain was supposed to obtain from his relationship with the Devil, as well as what he was expected to do for him. According to Jean's testimony, at least three times the Devil promised him money, and success in games. This gives a context for the later pact itself, written on playing cards.

For his part, Jordain agreed to steal some consecrated host from the Ciborium, which he was to break in pieces, wrap in a white napkin, and place in a pocket on his left side; he was then to take it to a place near Agen, where he would meet a man named Orpheure Huguenot, who would buy it from him; by doing this, the Devil promised, he would be fortunate in games and love. But he was caught on his way upriver to Agen, since one of the monks of the Church suspected him, and brought back to Blaye.

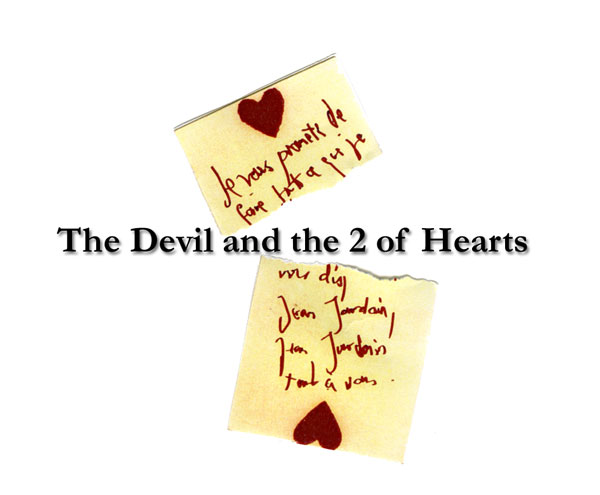

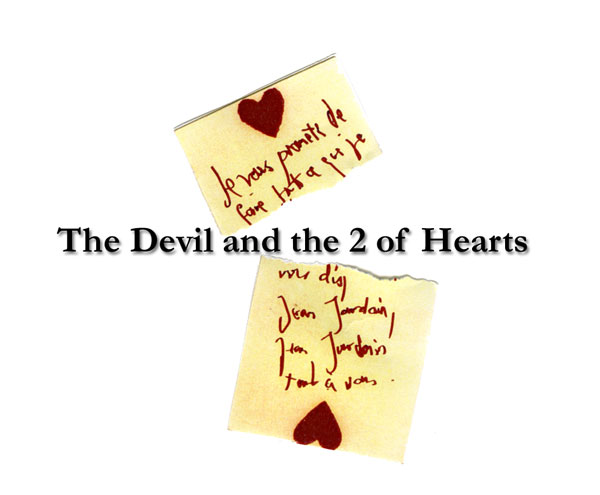

During questioning, not under torture, he gave a very long confession, and also told the judges where the pact that he had finally made was. Only the two of hearts was ever found, torn in two and buried in a field with sprouting grains.

On the card was written in blood, "I promise you to do everything I tell you, Jean Jordain, Jean Jordain, all for you." Despite the fact that the Four of Hearts was never found, both cards intrigued Pierre de l'Ancre enough for him to suggest that the Devil chose them for their symbolic value, and he speculated what that might be.

It is interesting that de l'Ancre interpreted the two of hearts in a way most of us would agree with. He suggests that the Devil "wanted the promise to be made on cards with two hearts shown, making a baneful alliance and joining together of his (heart) with that of the unfortunate (Jean Jordain)."

As for the Four of Hearts, de l'Ancre says that despite the fact that its contents are unknown, "it is well assured that it had these words, renouncing his Baptism, the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Mary Magdalene, and his Godfather and Godmother." The four hearts thus symbolized, in de l'Ancre's interpretation, Jordain's Christian identity, and his pact on the card symbolized his renunciation of that identity.

But two hearts can suggest another interpretation, that of indecision. De l'Ancre himself offers this interpretation of the card in his general introduction to the book, when he alludes to the story and suggests that the card was chosen by the Devil to remind Jordain that he could not serve two masters.

The Two of Hearts was torn, shredded and burned, and the pact declared null and void. The gravity of Jean Jordain's crimes to the sensibilities of the era is shown by his sentence: Jordain was to renounce and abjure his pact publicly, in the presence of the Curé of the parish and his Vicar, and before the church of the Holy Savior, he was to make honorable amend by begging pardon of God, the King and Justice; he had his fist (poing) cut off, was hanged and strangled, then burned; additionally, he had to pay 120 pounds (livres) in fines, of which 30 went to the King, 30 to the church of the Holy Savior, 30 to the convent of the Minimes, and 30 to the Hospital.

Note that de l'Ancre does not consider playing cards an evil in themselves, which was the normal Catholic position, unlike their reputation among some Protestants, such as Calvinists or philosophers like Pierre de la Primaudaye, who thought that the devil had invented them.

A further interesting point for historians of magic is that, given the legendary desperation of gamblers, this is surely the only known pact with the Devil ever written on playing cards. Surviving pacts, such as Urbain Grandier's (1590-1634), and instructions for making them, as found in some 16th and 17th century grimoires or magical textbooks such as "The Red Dragon", are made on clean parchment or papyrus. I know of no pact or instruction for making it that allows for anything else - although the details of the blood for Jean's signature are in perfect accord with tradition.

II. Corona and Isabella Bellochio

In roughly the same period, from 1589, the city of Venice gives two instances in which playing cards, in particular tarot cards, were used in magical rituals.

They come from the investigations of Ruth Martin published in her 1989 book, "Witchcraft and the Inquisition in Venice, 1550-1650" (Oxford, Blackwell, 1989). Martin's discovery was brought to the notice of tarot enthusiasts in 2000 by prolific internet tarot enthusiast Jess Karlin.

Ruth Martin demonstrates that the Inquisition's interest was in heresy, not magic. The latter was mortally sinful and criminal, but not heretical. The heresy, when it is noted, consists in worshipping the Devil, or profaning the sacraments. Magical rituals are only incidentally described.

The first account in which tarot cards are mentioned in connection with a love magical ritual comes from January of 1589. Isabella Bellochio was found guilty of being "formally apostate from God, having with works shown herself to believe that it was permissible to offer reverence to the devil, burning him lamps for several months continuously, and praying to him that he should make (her) lover come, and having a pact, if not explicit, at least tacit with that same devil" (Martin, 163-164). What that worship consisted of was given in a deposition by Bellochio's housemaid Marina, who testified that Bellochio "had worshipped an image of the devil by kneeling before it, with her hair loose, while maintaining a lantern alight before it day and night. '(She had)... a light (cesendello) which burned continuously in the kitchen in front of a devil and the tarots...'" (Martin, 163).

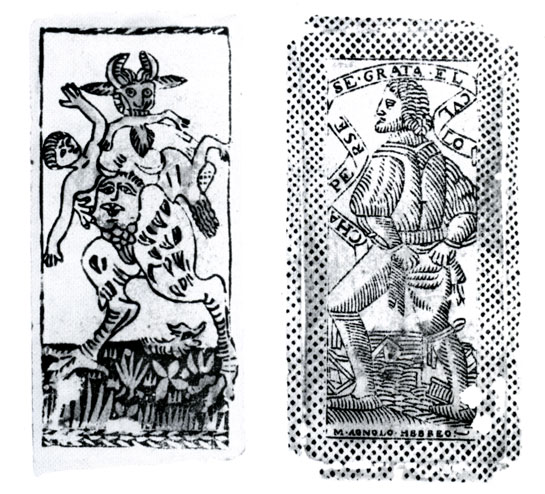

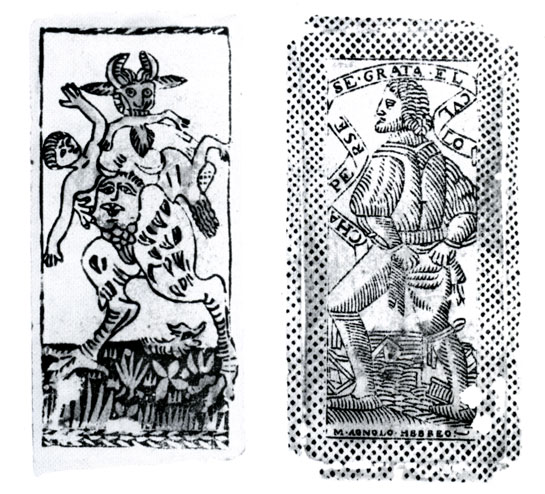

It is startling and incongruous to see "the tarots" mentioned in this context, and we wonder what exactly it might mean. Did she worship the image of the Devil from a tarot pack (which might or might not have resembled this 16th century tarot card, the only surviving one of cardmaker Agnolo Hebreo),

or was the image a homemade statue, and the tarot pack simply an accoutrement with an unstated purpose? We don't know, and I have been unsuccessful in finding Martin to ask her for more details.

In any case, whatever the purpose of the tarots in this instance, what interested the inquisitors was Bellochio's use of the cesendello lamp, which was the lamp normally kept burning in front of the reserved host, the very body of Christ. This worship, and the tacit pact it implied in the theology of the witch hunters, made her a heretic.

The second mention of tarot cards was recorded in a trial from the same year, in October 1589. In this case, a witch named Angela had apparently "told her client Corona that '... you need to adore the devil if you want to get help', and had suggested getting hold of a tarot card." (Martin, 162). In light of the greater detail preserved in the first case above, it is hard not to think that this card would have been the Devil.

Unless the Inquisition had recorded these incidental mentions of tarot cards, we would have no idea that such things were done with them in the context of folk magic rituals. Martin makes the point that for Christians of the time, the Devil was seen as a recourse for less-than-noble magical aims, while prayer to God was reserved for higher aims. Given the harsh penalties for being discovered invoking the Devil for magical purposes, it is not surprising we don't have more testimonies of it.

III. Leland

These Inquisition accounts from the 16th century have a curious echo in the only other folk magical use of tarot cards that I have found, that comes from much later, the nineteenth century, in a magical spell recorded by Charles Godfrey Leland in "Roman Etruscan Remains in Popular Tradition" (New York, Scribner, 1892

<http://www.sacred-texts.com/pag/err/err10.htm>). He writes "Jano is a spirit with two heads, one of a Christian, and one of an animal, and yet he hath a good heart, especially that of the animal, and whoever desires a favour from them should invoke (deve pregarle) both, and to do this he must take two cards of a tarocco pack, generally the Wheel of Fortune and the 'diavolo indiavolato', and put them on the iron (frame) of the bed, and say - 'Thou Devil who art chief of all the fiends! I will crush thy head until the the spirit of Jano Thou callest for me!' (Leland, 130).

"Diavolo indiavolato" means "bedeviled devil"; I'm not sure what that indicates, but I imagine it could mean that the Devil card was covered by the Fortune card, or perhaps it was turned upsidedown. Or perhaps, Leland has garbled his informant's words, and the spell itself is the bedevilment of the Devil.

This practice illustrates the attitude of a witch to the Devil, and might reflect what was being done in secret three centuries earlier. Although Leland's account was written long after tarot cards had become the subject of esoteric speculation (Leland's work must be used with caution in any case, at least for Aradia), this magical use seems to me to represent genuine folk-magic untainted by occult doctrines invented in the 18th century or later. It has a folkloric ring of truth to it.

THE DEVIL AND THE TWO OF HEARTS

Some new documentary discoveries of magical or "superstitious" use of cards from the earliest centuries deserve to be shared with the IPCS. These are not isolated or unexpected uses, when understood in the context of the early use of printed images. The material can be divided into two broad areas - devotional use and magic, and divination. While this is an arbitrary distinction, since divination is a category of magic, it helps me present the material.

I. Jean Jordain

The title for my talk comes from the following story about Jean Jordain. Jean Jordain was a young man who was tried in 1614 for witchcraft and sacrilege, part of which was making a pact with the Devil on two playing cards, a two and a four of hearts.

The trial of Jean Jordain took place in Blaye, on the Gironde north of Bordeaux in 1614. An account of the events was related by Pierre de l'Ancre in 1622, in his book "L'incredulite et mescréance du sortilège, plainement convaincue" (The disbelief and misbelief in witchcraft, plainly convinced).

Pierre de l'Ancre was born in Bordeaux in 1553. He studied law and philosophy in France, Bohemia and Turin. He became councilor to the Bordeaux parliment at the age of 29 in 1582, and in 1588 he married Michel de Montaigne's grand-niece. He was well acquainted with the leading intellectuals and political figures of his day. Because of his familiarity with the region, in 1609 Henri IV sent him to find and prosecute witches in the district of Labourd, in the extreme south-west of France. Travelling with another judge, de l'Ancre found the region completely infected with witches, and by the end of their inquisition, about 500 people had been burned at the stake for it.

The context of the period is described by Joseph McCabe, in his 1948 book "A History of Satanism". It should be remembered that at this time witchcraft was seen as a vast and unified movement of Devil-worship, an anti-religion.

"[The prominent jurist] Boguet condemned the use of torture, and L'Ancre and his colleague, another eminent judge and royal counsellor, used it only in two or three out of many hundreds of cases. At first they encountered a baffling silence. The priests, who wore swords and picturesque costumes and drank and danced with the villagers and townsfolk, were—it transpired—in the movement and instructed folk to say nothing. Large numbers of the women took to the sea in their husbands' boats or went on pilgrimage to Spain; where the cult was even stronger. At last, by torture or more amiable means, the judges won the confidence of a 17-year-old and fiery beggar girl—she danced the witch-dances for them—and they broke the conspiracy of silence. Here we have a competent lay judge reporting, without using torture, just the same chief phenomena as the Inquisitors. Some of the highest nobles and most of the priests attended the Sabbaths, and the priests said Black Masses. At one place there was a gathering of 12,000 witches. Educated women in their later 20's told how Satanism was the best religion, and they would rather go to the Sabbath, the "real Paradise," than to the Mass. It was a foretaste of their joy in the next life. This referred to the usual orgy of promiscuity. The Sabbaths, to which they took about 2,000 children to be initiated, were held nearly every night and sometimes during the day. As the trials proceeded the large fleets of fishing boats came in from the Atlantic, and the anger of the men at the prosecution seems to have forced the judges to close it prematurely. But, says L'Ancre, "an infinite number (really about 500, including several priests) were burned at Bordeaux and in Brittany"—which suggests that the cult spread along the coast. In fact, there were almost simultaneous persecutions on a large scale all over France. At Macon the jails were full, and there were trials at Orleans and other places."

Additionally,

"Whole communities of nuns were said to have been surrendered to the Devil. From Marseilles in 1611, the year after L'Ancre's inquiry, it was announced that the Ursuline nuns in one of the most respectable convents were dealing with the devil, and a number of them were "possessed.""[End]

Religious hatred was also in the air. By this time, the Edict of Nantes in 1598 had only recently stopped the bloodshed and destruction of the Hugenot wars, which had ravaged relations between Protestants and Catholics since 1562. Tensions were still rife, and both sides considered the other in league with the Devil.

It is this paranoid context that the trial of Jean Jordain took place. (the italicized text was summarized)

Pierre de l'Ancre devotes 20 pages to the story in his book - here are the essential details.

Jordain was born around 1589 in the small village of Moras near Agen. In March of 1614, at the age of 25, he was working as chamberlain to the lord of Castanet, Monsieur de Barastre. Jordain fell in love with the children's nanny, and proposed marriage to her, swearing, according to de l'Ancre, that the "Devil could take him if he didn't fulfill his promise to marry her". De l'Ancre takes this a darkly prophetic. The girl accepted and they consummated their love. But Jordain's affections seem to have changed, when the girl believed she had become pregnant. She entreated him to marry her immediately, but he continually urged her to have patience.

She soon realize that Jordain had no intention of marrying her, and in tears and rage appealed to Monsieur de Barastre to intervene. Sensing that he would be severly punished, Jordain fled to his family, and then, still feeling in danger, he went to Blaye, where he had earlier served the prior of the Church of the Holy Saviour, a Pierre de l'Espine.

His conscience continued to torment him, however, and he took long walks alone to clear his mind. About three weeks after his arrival in Blaye, during one of his pensive walks, he was suddenly afflicted with a massive head-ache, and saw a thick black fog in front of him.

Out of this fog walked "a man who appeared all hunched over, dressed in a robe of black silk, of medium height and sturdy, having a long beard and black hair, which like straps, blowing across his shoulders and face. He seemed blind in the right eye, without a cloak, a sword at his side, with bare feet." It was the Devil, Satan himself.

On this first meeting, which lasted about an hour, the Devil cajoled Jean with promises and finally presented a pact for him to sign, which Jean, being illiterate, could not read. The Devil said he could help him learn to read and write, but it would be enough for him to copy the pact letter by letter. Jean wouldn't do it, and finally, he began to go away, and finally, with a terrible smell - Jean said "Jesus Maria, you stink something awful!" - the Devil departed, promising to come back next Saturday at the same time.

He had several more meetings with the Devil, and it is interesting to see the rewards Jordain was supposed to obtain from his relationship with the Devil, as well as what he was expected to do for him. According to Jean's testimony, at least three times the Devil promised him money, and success in games. This gives a context for the later pact itself, written on playing cards.

For his part, Jordain agreed to steal some consecrated host from the Ciborium, which he was to break in pieces, wrap in a white napkin, and place in a pocket on his left side; he was then to take it to a place near Agen, where he would meet a man named Orpheure Huguenot, who would buy it from him; by doing this, the Devil promised, he would be fortunate in games and love. But he was caught on his way upriver to Agen, since one of the monks of the Church suspected him, and brought back to Blaye.

During questioning, not under torture, he gave a very long confession, and also told the judges where the pact that he had finally made was. Only the two of hearts was ever found, torn in two and buried in a field with sprouting grains.

On the card was written in blood, "I promise you to do everything I tell you, Jean Jordain, Jean Jordain, all for you." Despite the fact that the Four of Hearts was never found, both cards intrigued Pierre de l'Ancre enough for him to suggest that the Devil chose them for their symbolic value, and he speculated what that might be.

It is interesting that de l'Ancre interpreted the two of hearts in a way most of us would agree with. He suggests that the Devil "wanted the promise to be made on cards with two hearts shown, making a baneful alliance and joining together of his (heart) with that of the unfortunate (Jean Jordain)."

As for the Four of Hearts, de l'Ancre says that despite the fact that its contents are unknown, "it is well assured that it had these words, renouncing his Baptism, the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Mary Magdalene, and his Godfather and Godmother." The four hearts thus symbolized, in de l'Ancre's interpretation, Jordain's Christian identity, and his pact on the card symbolized his renunciation of that identity.

But two hearts can suggest another interpretation, that of indecision. De l'Ancre himself offers this interpretation of the card in his general introduction to the book, when he alludes to the story and suggests that the card was chosen by the Devil to remind Jordain that he could not serve two masters.

The Two of Hearts was torn, shredded and burned, and the pact declared null and void. The gravity of Jean Jordain's crimes to the sensibilities of the era is shown by his sentence: Jordain was to renounce and abjure his pact publicly, in the presence of the Curé of the parish and his Vicar, and before the church of the Holy Savior, he was to make honorable amend by begging pardon of God, the King and Justice; he had his fist (poing) cut off, was hanged and strangled, then burned; additionally, he had to pay 120 pounds (livres) in fines, of which 30 went to the King, 30 to the church of the Holy Savior, 30 to the convent of the Minimes, and 30 to the Hospital.

Note that de l'Ancre does not consider playing cards an evil in themselves, which was the normal Catholic position, unlike their reputation among some Protestants, such as Calvinists or philosophers like Pierre de la Primaudaye, who thought that the devil had invented them.

A further interesting point for historians of magic is that, given the legendary desperation of gamblers, this is surely the only known pact with the Devil ever written on playing cards. Surviving pacts, such as Urbain Grandier's (1590-1634), and instructions for making them, as found in some 16th and 17th century grimoires or magical textbooks such as "The Red Dragon", are made on clean parchment or papyrus. I know of no pact or instruction for making it that allows for anything else - although the details of the blood for Jean's signature are in perfect accord with tradition.

II. Corona and Isabella Bellochio

In roughly the same period, from 1589, the city of Venice gives two instances in which playing cards, in particular tarot cards, were used in magical rituals.

They come from the investigations of Ruth Martin published in her 1989 book, "Witchcraft and the Inquisition in Venice, 1550-1650" (Oxford, Blackwell, 1989). Martin's discovery was brought to the notice of tarot enthusiasts in 2000 by prolific internet tarot enthusiast Jess Karlin.

Ruth Martin demonstrates that the Inquisition's interest was in heresy, not magic. The latter was mortally sinful and criminal, but not heretical. The heresy, when it is noted, consists in worshipping the Devil, or profaning the sacraments. Magical rituals are only incidentally described.

The first account in which tarot cards are mentioned in connection with a love magical ritual comes from January of 1589. Isabella Bellochio was found guilty of being "formally apostate from God, having with works shown herself to believe that it was permissible to offer reverence to the devil, burning him lamps for several months continuously, and praying to him that he should make (her) lover come, and having a pact, if not explicit, at least tacit with that same devil" (Martin, 163-164). What that worship consisted of was given in a deposition by Bellochio's housemaid Marina, who testified that Bellochio "had worshipped an image of the devil by kneeling before it, with her hair loose, while maintaining a lantern alight before it day and night. '(She had)... a light (cesendello) which burned continuously in the kitchen in front of a devil and the tarots...'" (Martin, 163).

It is startling and incongruous to see "the tarots" mentioned in this context, and we wonder what exactly it might mean. Did she worship the image of the Devil from a tarot pack (which might or might not have resembled this 16th century tarot card, the only surviving one of cardmaker Agnolo Hebreo),

or was the image a homemade statue, and the tarot pack simply an accoutrement with an unstated purpose? We don't know, and I have been unsuccessful in finding Martin to ask her for more details.

In any case, whatever the purpose of the tarots in this instance, what interested the inquisitors was Bellochio's use of the cesendello lamp, which was the lamp normally kept burning in front of the reserved host, the very body of Christ. This worship, and the tacit pact it implied in the theology of the witch hunters, made her a heretic.

The second mention of tarot cards was recorded in a trial from the same year, in October 1589. In this case, a witch named Angela had apparently "told her client Corona that '... you need to adore the devil if you want to get help', and had suggested getting hold of a tarot card." (Martin, 162). In light of the greater detail preserved in the first case above, it is hard not to think that this card would have been the Devil.

Unless the Inquisition had recorded these incidental mentions of tarot cards, we would have no idea that such things were done with them in the context of folk magic rituals. Martin makes the point that for Christians of the time, the Devil was seen as a recourse for less-than-noble magical aims, while prayer to God was reserved for higher aims. Given the harsh penalties for being discovered invoking the Devil for magical purposes, it is not surprising we don't have more testimonies of it.

III. Leland

These Inquisition accounts from the 16th century have a curious echo in the only other folk magical use of tarot cards that I have found, that comes from much later, the nineteenth century, in a magical spell recorded by Charles Godfrey Leland in "Roman Etruscan Remains in Popular Tradition" (New York, Scribner, 1892

<http://www.sacred-texts.com/pag/err/err10.htm>). He writes "Jano is a spirit with two heads, one of a Christian, and one of an animal, and yet he hath a good heart, especially that of the animal, and whoever desires a favour from them should invoke (deve pregarle) both, and to do this he must take two cards of a tarocco pack, generally the Wheel of Fortune and the 'diavolo indiavolato', and put them on the iron (frame) of the bed, and say - 'Thou Devil who art chief of all the fiends! I will crush thy head until the the spirit of Jano Thou callest for me!' (Leland, 130).

"Diavolo indiavolato" means "bedeviled devil"; I'm not sure what that indicates, but I imagine it could mean that the Devil card was covered by the Fortune card, or perhaps it was turned upsidedown. Or perhaps, Leland has garbled his informant's words, and the spell itself is the bedevilment of the Devil.

This practice illustrates the attitude of a witch to the Devil, and might reflect what was being done in secret three centuries earlier. Although Leland's account was written long after tarot cards had become the subject of esoteric speculation (Leland's work must be used with caution in any case, at least for Aradia), this magical use seems to me to represent genuine folk-magic untainted by occult doctrines invented in the 18th century or later. It has a folkloric ring of truth to it.