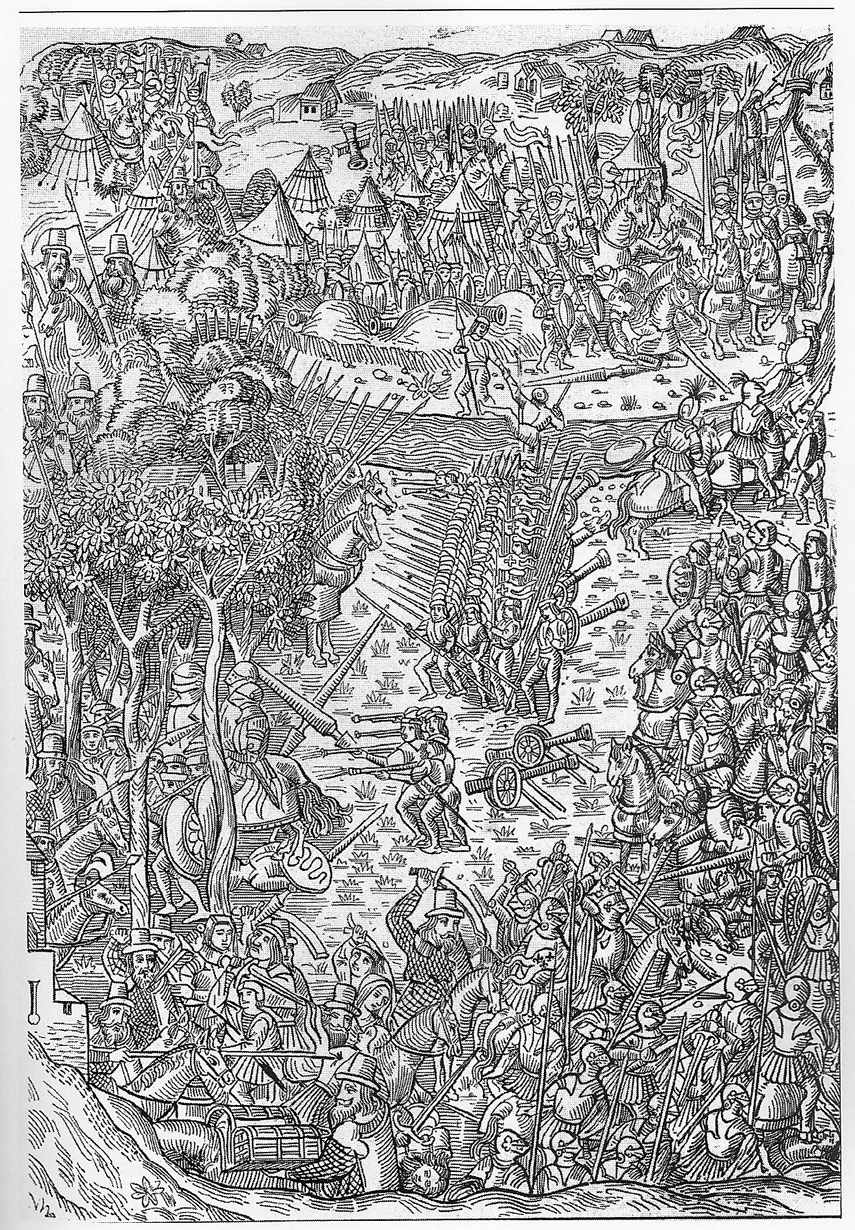

this looks quite convincing. and in the picture again we see "normal" fighting - nothing special indicating either domination or foolishness.

so it seems that the french invasion story is unfounded - i am ok with that - including the taro river link.

...

... hm .. I don't know, how you conclude this. I haven't even understood, what Ross thought, what the terminus "French invasion theory" shall be.

Actually he speaks of different ideas:

The first person I know of to suggest the Taro theory in any form is Paul Lacroix (pseudo. For P.L. Jacob), L’origine des cartes à jouer (Paris, 1835), p. 7:

“Le nom de tarots dérive de la province lombarde, Taro, où ce jeu fut d’abord inventé.”

(The name tarots comes from the Taro region of Lombardy, where this game was first invented.)

Well, that's a production in the region Taro ... this is not a French invasion idea.

The second is Sylvia Mann, Collecting Playing Cards (Arco, 1966) p. 28:

“My own theory is that these cards were either invented or popularized in the Valley of the Taro river (a tributary of the Po) which runs remarkably close to the locality where some of the earliest tarot cards are known to have existed.”

That's another production idea.

For the French invasion theory, but without reference to the Battle of Fornovo (Taro) specifically, Dummett summarizes (Game of Tarot, page 407): “The period of the French incursions into Italy, from 1494 to 1525, may therefore well have been the time when the game of Tarot first entered France.”

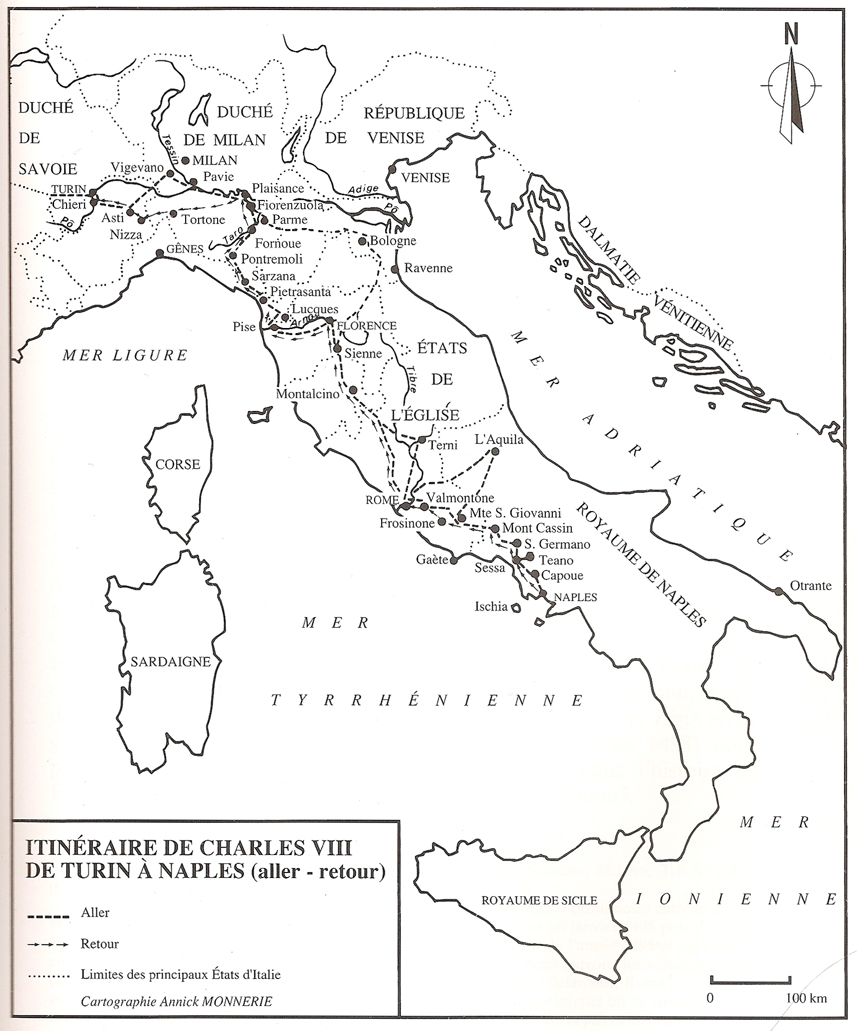

We know now that this time-frame must be considerably shortened, since packs and woodblocks of the cards were already being exported from Avignon to Pinerolo (near Turin) in 1505.

So the argument must become “The period of the French incursions into Italy, from 1494 to before 1505, may well be when the game of Tarot first entered France.”

So this shall be one real French invasion theory (about cards, about the use of the word ?) Ross arguments, that Dummett's very global position (1494 - 1525) should be reduced cause the 1505 document of Avignon. But: Avignon wasn't France. Pinerolo wasn't France.

And Avignon and its production had following conditions:

A well established playing card production till 1505. This more or less happened in a longer period, during which cardinal Giuliano de Rovere (later pope Julius II) ruled in Avignon ... so this cardinal wasn't a foe of playing cards, one may assume. Avignon as production city of playing cards clearly was manifested by the nearness of Lyon, which was the greater playing production center in this time, maybe the most important location in Europe in this aspect ... and btw. also called French capital in this period (Paris had lost some importance, France desired the invasion of Italy, cause Italy had become such an important place).

But Giuliano de Rovere was foe to Alexander VI, pope in Rome since 1492. He fled to France relatuively soon after Alexander was elected. So partly Giuliano de Rovere had been behind the French invasions 1494 and 1499. In 1503, Alexander died and Giuliano became Julius II, himself pope in Rome. But he surely hadn't lost all his connections in Avignon, where he had reigned about a period of c. 30 years. If we see, that Alfonso d'Este, new duke in Ferrara in 1505 made for his installation as new duke some Tarochi deck in June 1505, and in December 1505 a production followed in Avignon, then we can't exclude Julius II. (likely from Savona, which if half-France, half Italy in its culture) in this calculation, who naturally knew Alfonso and so probably "responded" to an Italian activity.

The general destiny of Avignon as a playing card production place went bad after Julius had left Avignon, and this already before Julius turned against the French in 1510. From this it seems, that the presence of cardinal Giuliano Rovere / later Julius was indeed rather important for the production in this city.

But do we have now a real production guarantee of Taroch or Taraux in France in 1505 ? No, not really.

But this special knowledge about the state of Avignon naturally doesn't answer, if a French Taraux production existed prior to 1505 or not. It simply leads to the condition, that we in the current research situation don't know.

Further there is no argument, how the word Taroch and later Tarot developed.

We've the values of "first appearances in documents, as far we now about them" for different things and there are:

1. a poem of Bassano Mantovana, who clearly is at "Milanese side" in mid 1490s, containing "Tarochus" (no playing card connection)

2. a poem of Alioni d'Asti, who clearly is at "French side" in mid 1490s, containing "Tarochus" (no playing card connection)

3. 3 card productions notes in 1505, two in Ferrara and one in Avignon, containing "Tarochi" in Ferrara

4. a battle at the river "Taro" at 6th of July 1495

5. Stephen's suggestion, that "Tarocch" is a used word in Milanese-Italian dictionaries from c. 1600. As evidence for a use of Tarocch prior to 1495 isn't delivered for the moment, it somehow mst be ignored in the moment.

My thesis is that the battle caused the use of "Tarochus" by two poets, who were known to each other (at least it is clear, that Alione knew Bassano, cause he titled a work "Macarronea contra macarroneam Bassani") and both poets fall in the category in "poets active in Macaroni literature", which is a form in which vernacular words are mixed with Latin words or endings.

Macaronic Latin specifically is a jumbled jargon made up of vernacular words given Latin endings...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macaronic_language

If we look now at "Tarochus", then we perceive, that it has a Latin ending. Also it's clear, that "Macaroni poets" are naturally good word inventors, so just ideal to use words for a "first time".

So we have a vernacular "Taro" (name of a river) and a Latin ending "-us". Missing is the combining "-ch-".

************

Now there had been another invasion of something French short before 1494, which happened more or less mainly with some intensity in the 1470s. This was the Saint Rochus cult. French "St. Roch", Italian "Rocco", in Latin "Rochus", similar as we meet "taroch, tarocco and tarochus forms in this other questions.

A French pilgrim to Rome from Montpellier, France, normally. He got the plague, and he survived it, and so he became a saint ... giving hope to other also to survive the plague.

French soldiers in 1494/95, who survived all battles and also that of the river Taro, often gave this impression:

Although there's a 1484 at this colored engraving , there is agreement, that it is from 1496 and by Dürer. I remember dark, that the "1484" is considered to have been given cause a bad prophesy in 1484 (or something like this). The picture shall show a victim of Syphilis ... and that was, what many French soldiers got, when they returned from Naples. And Syphilis was just a new plague, so the association to St. Rochus (who definitely had a height of popularity in this time and French connection) is rather natural.

Poets play with words, and occasionally with words, which were never used before, that's a common feature in literature. Forming from Taro and St. Rochus and macaronic inspiration Tarochus isn't a big act.

Mostly such inventions haven't a big success, but occasionally they have. They become then part of language.

Now let's look at one of the poets, and what he really did:

Ad magnifiais dominus Gasparus Vescontus (the honored person, which is of importance in Milan, who died 1499; so that's part of the dating "before 1500"), de una vellania que fuit mihi Bassanus de Mantua (that's the poet himself) ab uno Botigliano Savoyno (this is identified as a porta Botigliano in Vercelli with "Quidam Vercellis stat a la porta Botigliano" in the text

Omnes qui Sessiam facit pagare passantes) apud uncellis, et de una piacevoleza que ego Bassanus fecivi sibi Botigliano.

Unam volo tibi, Gaspar, cuntare novellam

Que te forte magno faciet pisare de risu.

Quidam Vercellis stat a la porta Botigliano

Omnes qui Sessiam facit pagare passantes ;

Et si quis ter forte passaret in uno,

Ter pagare facit : quare spesse voltas eunti

Esset opus Medicis intratam habere Lorenzi,

Hic semper datii passegiat ante botegam,

In zach atque in lach culum menando superbe

Quod sibi de Mutina cum vadit Pota videtur,

Qui de cavalo dicitur seminasse fassolos ;

Sed si cercares levantem atque ponentem

Non invenies quisque poltronior illo ;

Non habet hic viduis respectum nec maritatis

Sed neque pedonihus, nec cavalcantibus, omnes

Menat ad ingualum sicut lasagnia natalis ;

Nec pregat (ut ceteri faciunt) pagare, sed ipso

Sforzat, et illius vox est hec unica : Paga.

Iste manegoldus me vidit a longe venire,

Nec mora, corivit ceu mastinacius unus

Et non avertentis prendit per brilia cavallum.

De montilio quidem parlabam ac ipse zenevra ,

Cujus putinam mihi marchesana locavit,

Et brevitas sensus fecit conjungere binos,

Territus at quadrupes sese drizavit in altum ,

In pedibus solum se sustentando duobus.

Crede mihi non est illo Gasparre, cavallo ,

A solis ortu spaurosior usque ad occasum.

Tene manus ad te, dixi , villane cochine.

Ad corpus Christi, faciam cagare budellas,

Si tibi crepabit, respondit, barba pagabis.

Quis tibi pagare negat, poltrone? dicebam :

Quis poltronus ego? Tu. Mi? Si. Deh rufiane.

Erat mecum mea socrus unde putana

Quod foret una sibi pensebat ille tarochus,

Et cito ni solvam mihi menazare comenzat.

Tune ego fotentis animosus imagine mulli,

Gaspar, eum certe volui amazare : sed ego

Squarcinam nunquam potui cavare de foras.

Ille manum cazare videns ad arma : comenzat

Fugere tam forum quod apena diceres amen,

Parebatque anima de purgatorio cridans :

Altorium , altorium , misericordia Jesus !

Et sic cridando sese in botheca ficavit,

Tam plane quod nasum sboravit contra pilastrum.

Ille sibi videns sanguem uscire de naso,

Me ratus est illam stultus fecisse feritam ,

Et qui debueram strictus stare sicut agnellus;

Non ego negabam unus fecisse ribaldo :

Talia sed tantum dedi sibi vulnera quantum

Que sibi prima fuit dosso vestita camissa.

Inde valenthomus volens cum spata parere

Andavi Sesiam versus bravosando cavallum ,

Atque ego dicebam mecum passando riveram,

Pro quaranta tribus vadat rumor iste quatrinis,

Vos mihi vicino fecit pro ponte pagare[ (paying to cross the bridge),

Et nunquam pontem, neque ponticella passavi.

Ad eundem disticon cordat :

Sobrius hec oro ne legeris, optime Gaspar,

Carmina ; cenato scripsimus ista tibi.

We've a place (Porta Botigliano at Vercelli) and we have a bridge: And a "tarochus" (whatever this means) demanding money for crossing the bridge and we have Bassano, who doesn't like to pay.

Then we have Bassano getting furious, and the demanding Tarochus getting fear, and then stumbling about his own feet in his attemt to escape.

Nonetheless Bassona doesn't cross the bridge (as far I understood, what was going on).

Vercelli is situated West of the river Sesia between Milan and Turin and belonged to Savoy. At the other Eastern side of the river is territory controlled by Milan - at least in 1495, and that's the time, which interests us.

Then, just this year, Vercelli became the center of Italian attention in Setember 1495, cause Milan negotiated with France, what should happen next.

Milan had been Pro-French for a longer time of the invasion to Italy. But then - with the fight of the Italian league at river Taro - Milan changed its sides and opposed France. A major undecided problem in the negotiations was the French occupation of Novara west of the river Sesia ... about 22 km away.

http://maps.google.com/maps?oe=utf-...code_result&ct=image&resnum=2&ved=0CD4Q8gEwAQ

Novara was taken under siege by Milanese troops already earlier and the conditions of the French soldiers in the city were bad, very bad. And with each day of the negotiations the conditions became worse.

It seems plausible to assume, that the poem wasn't written before and the connected story didn't happen before ... why should the Milanese poet Bassano have trouble or cause trouble, when he entered Savoy, when Savoy had an alliance with France and France had an alliance with Milan?

No, the trouble should have happened likely during the unusual situation of the negotiations. These negotiations took a longer time, naturally Milanese persons should have been in Vercelli and naturally they demanded free entrance and wouldn't pay for crossing bridges.

http://www.third-millennium-library.com/readinghall/GalleryofHistory/BEATRICE_D_ESTE/24.html

Immediately after Fornovo (6th of July 1495), the Count of Caiazzo's cavalry had joined his brother Galeazzo's force before Novara, and on the 19th of July (1495)[ the Marquis of Mantua encamped under the walls with the Venetian army. The garrison of the besieged city was six or seven thousand strong, and well provided with arms and ammunition, but already supplies of food were scarce, and men and horses were dying of sickness and hunger.

...

A council of war was held, and Lodovico's recommendation to blockade the town instead of carrying it by assault was finally adopted. On the 5th of August the duke and duchess were present at a grand review of the whole army, which, with Galeazzo's troops and the German and Swiss reinforcements, now amounted to upwards of forty thousand men. (40.000 against 6000-7000 in Novara).

...

In vain Louis of Orleans and his famished soldiers looked out for the French army that was to bring them relief. King Charles had gone to visit his ally the Duchess of Savoy at Turin, and was consoling himself for the toil and disappointments of the campaign by making love to fair Anna Solieri in the neighbouring town of Chieri. Since his reduced forces were unequal to the task of facing the army of the league and relieving Novara, he sent the bailiff of Dijon to raise a body of twelve thousand Swiss in the Cantons friendly to France, and decided to await their arrival before he took active measures.

Meanwhile he and most of his followers were thoroughly tired of warfare, and the queen never ceased imploring him to return home.

....

But Briconnet, the Cardinal of S. Malo, Lodovico's old enemy and a staunch partisan of Orleans, defeated these plans by his intrigues, and the French army, leaving Asti, advanced to Vercelli, in the duchy of Savoy, and prepared to take the field. Both parties, however, were growing weary of this prolonged warfare, and Commines declares that in the French camp no one wanted to fight, unless the king led them to battle, and that Charles himself had not the slightest wish to take the field.

At length, early in September, the first detachment of Swiss levies reached Vercelli, and on the 12th the king himself arrived in the camp (this seems to say, the the French king was now in Vercelli). His first act was to hold a council of war, which decided in favour of peace, and Commines was sent to treat with the Marquis of Mantua. The allies insisted on the unconditional surrender of Novara, while Charles VIII. asked for the restitution of Genoa as an ancient fief of the French crown. Nothing was concluded, but a truce of eight days was agreed upon, and prolonged conferences were held at a castle between Vercelli and Cameriano (Cameriano is at the mid between Vercelli and Novara; so the castle should have 5-6 km distance to Vercelli, which might be Borgo di Vercelli, but somehow it seems to have been not the place; I think, that Milanese troops controlled all the region till the river then, without the exception of Novara itself; the negotiations partly took place at other places, so also in Cameriano in the duke's rooms).

...

The evacuation of Novara, however, was unanimously agreed upon, and on the 26th of September, Orleans and his garrison marched out with the honours of war, and were escorted by Messer Galeaz and the Marquis of Mantua to the French outposts. More than two thousand men had already died of sickness and starvation. Almost all their horses had been eaten, and the survivors were in a miserable plight. Many perished by the roadside, and Commines found fifty troopers in a fainting condition in a garden at Cameriano, and saved their lives by feeding them with soup. Even then one man died on the spot, and four others never reached the camp. Three hundred more died at Vercelli, some of sickness, others from over-eating themselves after the prolonged starvation which they had endured, and the dung-hills of the town were strewn with dead corpses. (I've read other reports, in which the state of the Novara troops was described with more drama.

...

Accordingly, on the 9th of October a separate convention was concluded between the King of France and the Duke of Milan, leaving the other Powers to settle their differences among themselves. Novara was restored to Lodovico, and his title to Genoa and Savona recognized, while Charles renounced the support of his cousin Louis of Orleans' claims upon Milan. In return the duke promised not to assist Ferrante with troops or ships, to give free passage to French armies, and assist the king with Milanese troops if he returned to Naples in person. He further renounced his claim on Asti, and agreed to pay the Duke of Orleans 50,000 ducats as a war indemnity, and lend the king two ships as transports for his soldiers from Genoa to Naples. A debt of 80,000 ducats, that was still owing to Lodovico, was cancelled, and the Castelletto of the port of Genoa was placed in the Duke of Ferrara's hands, as a security that these engagements would be kept on both sides. The (French) king, we learn from Commines, still retained a friendly feeling for the Duke of Milan, and invited him to a meeting before he left Italy; but Lodovico had taken umbrage at certain offensive remarks made by the Count of Ligny and Cardinal Briconnet, and excused himself on plea of illness, while he declared in private that he would not trust himself in the French king's company unless a river ran between them. "It is true," says Commines, "that foolish words had been spoken, but the king meant well, and wished to remain his friend."

(The French king invited, but Lodovico didn't ome, but surely some others of the Milanese party had followed the invitation ... otherwise this would have not very polite.)

From all this I would assume, that a greater Milanese delegation visited indeed the French king in Vercelli after the concluded peace, but not Ludovio himself. Bassano might have well have belonged to this group

I think, that an "after 1495" is possible, too, as the tensions between Milan and Savoy have had some constancy ... after 1495. But before ...? I would doubt that.

**********

The other text, which contains a "Taroch", is from Giovan Giorgio Alione, a promoter of French interests in Italy. The text is very difficult, as written in a rare old dialect near Asti.

Andrea Vitali has found the text and admits, that the text is very difficult.

http://www.letarot.it/page.aspx?id=264&lng=eng

Andrea promotes the text as "likely from 1494", about which I've doubts. All Alione texts have much later printing dates. True is, that Asti got great attention twice, once, when Charles VIII crossed it on his way to Italy and had some waiting there time there, but also, when he came back from Italy, so in 1494 and 1495, before and after the river-Taro-event.

The text is - if I understand Andrea correctly - full of sexistic associations. Syphilis has a certain association to sexual activities. If Syphilis was connected to the new word Taroch, the text would get a rather different interpretation ... the text contains details about the behavior of women, who cheat her husbands and the case of a flourishing Syphilis this might have bad consequences.